“OK, now can you smooth out those frown lines?” “There’s a bit of a double-chin thing happening too, nip that.” “Brighten up the undereye area, she looks like she has two black eyes.” “Take in the waist just a smidgen.” “Ah, don’t forget to remove the veins on the hands.” “Hmm, still not 100% happy with the face, can you just smoothen it all out a bit more?” “Perfect.”

The above is basically the standard string of requests a graphic designer hears from an editor. Much ink has been spilled about the use of Photoshop in the industry, but whereas we’ve been made to believe it’s a type of high-level sophisticated use for large-scale ad campaigns, it’s actually quite more rampant than that. Today, virtually anyone can edit their Instagram photos with apps as simple as Facetune. And does.

Facetune refines skin texture, smoothes the skin, removes lines, and even puts on makeup.

Whereas we were once only subject to highly edited images in print magazines, we now look at that editorial-level of imagery constantly on our laptops and phones. It’s no wonder that we’re growingly consistently at-risk for developing Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD) and spawning new related conditions such as muscle dysmorphia disorder (MDD) - a type of body dysmorphia marked by feeling insufficiently muscular or lean, when that is often far from the case. MDD affects mostly men, and according to Out magazine, has been exasperated from apps such as Grindr, and once again, Instagram.

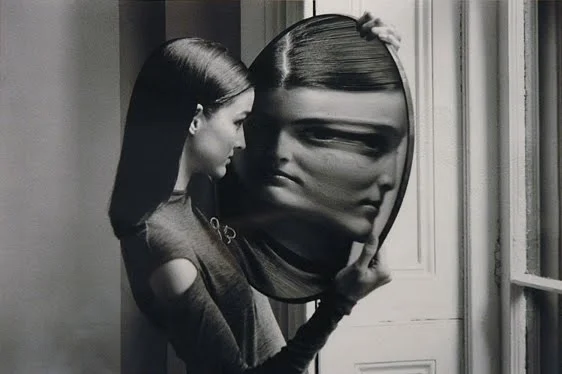

Carmen, who’s always been open about her issues with images and anorexia, admits that her struggle with body dysmorphia and anorexia started when she was just 14 years old, lasting until she turned 44. In that time, her weight dipped to a mere 42 kilos and she lost her period from lack of body fat, all in part because of a disconnect between the mirror and her mind. “I don’t see myself the way other people do,” she says.

Defined, BDD is an anxiety disorder in which a person has an often debilitating preoccupation with perceived flaws in his or her appearance. What one sees in the mirror is a distortion of reality, exaggerating faults and creating the appearance of defects that aren’t really there – though they appear real to the individual. According to the BDD foundation, symptoms include, but are not limited to:

- Checking features repeatedly in a mirror or reflective surface

- Picking at skin or feeling skin with fingers; obsessing about wrinkles, texture and pores

- Discussing one’s appearance with others

- Disguising or camouflaging oneself or one’s appearance

- Comparing oneself to models in magazines or other, seemingly “better looking” people

Much like with anorexia, individuals with BDD experience the dysmorphia of seeing a dissatisfying or exaggerated shape that disagrees with their true figure. The two disorders, while distinct, share common symptoms and a high level of co-morbidity (often occurring together) including distorted perception, emotional distress, anxiety, and disgust with their looks. Clinical solutions to BDD and anorexia often include cognitive behavioral therapy and anti-anxiety medication, but at first it's key to simply gain awareness about your distorted perception to avoid bold misguided decisions such as extreme dieting and repeat plastic surgery.

As an industry of perfectionists, after all, we're in the businesses of spotting inconsistencies, editing, and making people dream, we both fuel it and are uniquely dispositioned. People who tend to develop BDD have abnormalities in visual processing, they tend to overfocus on tiny details of a visual stimulus and are less able to see the ‘big picture’ than people without BDD. A highly useful trait in fashion.

Former Australian Vogue editor Kirstie Clements recalls being at a baggage carousel with a fellow fashion editor when she realized how much industry expectations can distort body image. “I noticed a woman standing nearby. She was the most painfully thin person I had ever seen, and my heart went out to her. I pointed her out to the editor who scrutinized the poor woman and said: ‘I know it sounds terrible, but I think she looks really great,’" she recalled.

And while it should be noted many women unfortunately suffer from what is known as “normative discontent” or a general dissatisfaction with their bodies, it can fairly easily morph into anorexia, bulimia or body dysmorphic disorder. Checking one’s appearance between 20 and 30 times or more a day, compulsive selfie taking and editing, and feeling consistently unconfident in or preoccupied by your features can be the beginning of body dysmorphia, and a sign that one is growing unbalanced.

Kim has been slimmed down, and her skin has been brightened and smoothened.

Carmen noticed the effects of magazines and their modified editorials early on. “I remember when I was younger in a psychology class studying in the 80s when my anorexia started,” she said. “I’ll never forget a study I read that found that people who read magazines like Time and National Geographic, that they would feel more empowered, and then the people reading fashion magazines, all of them start having self-esteem problems.” The results from the study, carried out by Robin Tolmach Lakoff and Raquel Scherr at Berkeley, have been replicated many times since.

Those affected by BDD and anorexia sufferer from distorted perception.

Although she is featured in them to promote her causes and businesses, Carmen refuses to buy fashion magazines out of awareness that they’ll reinforce her dysmorphia. Unlike Carmen, the average woman reads three magazines on a regular basis, and women working in fashion, or even with an interest in the industry, tend to read a few more titles, exposing themselves to more unrealistic images and hard-to-obtain aesthetics.

The pioneering work of Lakoff and Scherr in the 80s brought awareness to how the type of content we consume affects our perception.

One of the biggest challenges for the fashion industry is how to create aspiration without having such a negative impact on people. “Our mission in Vogue’s fashion pictures is to inspire and entertain…not to represent reality”, Alexandra Shulman, former British Vogue Editor-in-Chief, has said. Yet inspiration begets aspiration, and consumers want to live the editorial. Is there a way to stay sufficiently grounded to still aspire and work on yourself without it becoming dysfunctional?

Carmen believes that the antidote to BDD is to learn to derive your sense of worth from something other than your appearance. For Carmen, books, nature, and spending time alone, reconnecting the body and the mind helps most. "I don’t focus on my body unless I see a picture of it. I feel empowered from the soul, not from the body. I embrace my body, but I know that like any asset, it deteriorates, but my soul doesn’t. I get my sense of power from my soul. If I receive a compliment, I accept it graciously, but try and focus on something else as to not reinforce the ego." This kind of mind-body awareness has taken years to cultivate, but even 10 minutes of meditation per day will help anyone disconnect from the mind's obsessive appearance-related thoughts.

In the height of her dysmorphia, Carmen avoided seeing pictures of herself but she actually now credits Instagram as a tool of empowerment that helps her see herself more realistically and learn to be happy with it. “I still recognize that I have body dysmorphia, but I know it’s my dysmorphia and I’m aware that I have it,” said Carmen. “I know it’s not real.”

Featured photo: Thomas Northcut and GNM Imaging/guardian.com