Photo: fashionista.com

Two weeks ago, between crystalline bows, pearl brows, and ink-dipped fingers under starburst hand jewelry, model Alana Henry emerged in a fur bomber jacket with ballooning sleeves crisscrossed in Gucci Gs for the brand’s Resort ‘18 presentation. Social media alit. First, with praise for the collection, then with a caveat. When side-by-sides of Dapper Dan’s 1988 creation for Diana Dixon and Gucci’s latest offering appeared, eyebrows rose at the similarities between the two. But neither Alessandro Michele nor Dan is a stranger to appropriation. Dan made his name bootlegging logos from designers and incorporating them into his own designs, while Michele collaborated with and pulled inspiration from Gucci Ghost and Coco Capitán before “paying homage” to Dan.

In light of Michele’s puff-sleeved lookalike of the Dapper Dan original, the industry is up in arms over what separates inspiration from appropriation, and imitation from badly disguised borrowing. Of course, how thick the lines are between each depends on the lens you view them in, particularly if that lens is a knock-off. Imitation may be the sincerest form of flattery or the “ransom of success,” as Chanel would say, but in fashion, more often than not it’s a point of contention. Still, despite justified criticism, Gucci’s take on Dapper Dan might simply be one more facet in fashion’s complicated relationship with copying.

Photo: businessoffashion.com

Long before Twitter could call out copycats, Charles Worth was stitching labels into his gowns to stave off the stealing of his work. Likewise, even Chanel, a proponent for replication, took legal action against Suzanne Laneil for snatching her sketches in the 1930s. But today, intellectual theft isn’t always as concrete, or even punishable.

Unlike works of art, songs, and literature, designs aren’t typically subject to copyright. Instead, while trademark covers brand names and logos, actual designs and articles of clothing are unprotected as utilitarian goods. Julie Zerbo of The Fashion Law believes inaccessible or nonexistent copyright laws in the US make imitation unavoidable for designers. “Fashion is an industry that thrives off of inspiration — so much of what we see nowadays in fashion has been done before, and so I don’t think inspiration is bad thing,” she told Who What Wear. “I do think that imitation posing as inspiration is a bad thing.”

Today, this lack of protection leaves room for the much-maligned practice of fast fashion retailers ripping off runway looks, an almost expected practice. But when one designer seemingly redoes the look of another years later, that’s a different story.

Chanel Pre-Fall 2016 / Photo: qz.com

In 2015, after visiting French-Venezuelan designer Mati Ventrillon’s Fair Isle studio, Chanel showed replicas of the designer’s prints in its Métiers D’Art show mere months after seeing them. While this was a direct case of copying that the brand apologized for, others are not so cut and dry. Only days ago did Stefano Gabbana post a side-by-side of Dolce & Gabbana’s Grecian column heels from Resort 2014 and Chanel’s comparable electric blue style from Resort ‘18. Even while calling out Chanel for potentially copying his designs, Gabbana posted a mea culpa for recreating Vivienne Westwood’s 1989 SEX choker in 2003. Before that, the 90s saw Yves Saint Laurent sue Ralph Lauren for ripping off the “Le Smoking” jacket, only to later be accused by Christian Louboutin of stealing his shoes’ infamous red soles in 2011.

Dolce & Gabbana SS14 / Photo: vogue.com

Chanel Resort 2018 / Photo: fashionquarterly.com

In these cases, the collections were a handful of years apart, making the misappropriation ever more obvious. And while designers are always looking to the past for inspiration, there’s a thin line between paying homage and pilfering. Case in point: when Balmain’s Olivier Rousteing showed a design that mimicked a suit from Alexander McQueen’s debut collection for Givenchy, he was held accountable, but when Moschino’s SS13 collection read like an André Courreges editorial, it was seen as borrowing from the cultural archive.

A similarly complicated relationship exists between fashion designers and artists. Jeremy Scott has been known to be a repeat offender in infringement and, in 2012, was sued by mural graffiti artist, Rime, for copying “Vandal Eyes,” printing the design on suit jackets and Met Gala gowns without the artist’s consent.

Rimes' "Vandal Eyes" as a Moschino original / Photo: hypebeast.com

Yet for every blatant copycat, there’s a beautiful collaboration or derivative. While Scott was sued for the latter, his collections, like those emblazoning clothes with the Barbie logo and rebranding fast food chains, were praised. Likewise, YSL’s transformation of a Mondrian from a canvas to a silhouette and D&G’s superimposed 6th century mosaics could be seen as cultural copycats or offshoots of inspiration.

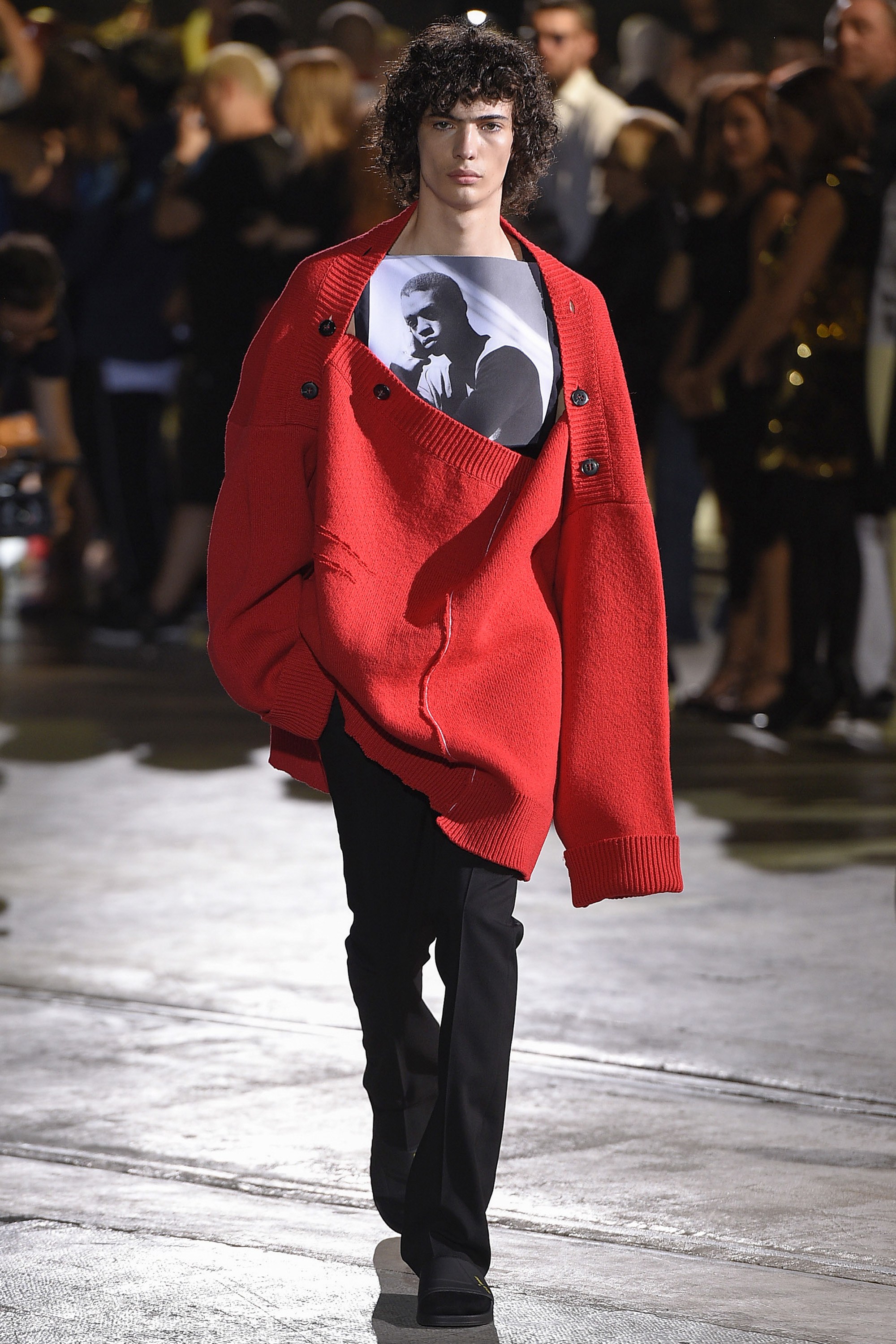

Some of the most memorable collections as of late came from fashion’s ability not to appropriate culture, but incorporate it. For SS14, Miuccia Prada commissioned muralists Miles ‘El Mac’ Gregor, Mesa, Gabriel Specter, and Stinkfish, and illustrators Jeanne Detallante and Pierre Mornet to convey femininity through portraits. The collection saw supersized women across torsos and along hems in a statement that preceded the pink pussy hat movement. Raf Simons often promotes the work of artists and photographers, as well, most recently in his SS17 Men’s collection where he featured Robert Mapplethorpe portraits throughout.

Prada SS14 / Photo: vogue.com

Raf Simons SS17 / Photo: vogue.com

Still, these are collaborations that are mutually beneficial, and appropriation is different from inspiration. All too often there’s a better-to-ask-for-forgiveness mentality in fashion where credit isn’t given where it’s due until it is too late (or until Twitter tells a designer to do so). Like with Gucci’s attempt to collaborate with Dapper Dan gone wrong, Alexander McQueen asked photographer Don McCullin for permission to print his images on clothes in 1996. McCullin refused, but you wouldn’t know that to look at McQueen’s Dante collection. Today, many credit the collection for “making” McQueen, but part of what made the collection was the work of someone else – and how McQueen used it.

Like sampling hit singles to produce a new track, borrowing in fashion produces new ideas. But for the best tracks, credit is always given where credit is due. In fashion, for the cut-and-paste culture to continue, it comes down to respecting the cultures, designers, and artists the ideas are derived from. Otherwise, it’s just a knockoff – and nobody likes that.

.